On 24 May, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) ended an executive meeting in Quebec, Canada. Among the topics on the docket was the selection of potential host cities for the 2020 Summer Olympics. Of the five “applicant cities” submitting bids for consideration–Baku, Doha, Istanbul, Madrid and Tokyo– Baku (Azerbaijan) and Doha (Qatar) were not selected to proceed to the “candidate” phase of the bidding process. After losing a bid for the 2016 games (to Rio de Janeiro), this marks Doha’s second unsuccessful Olympics bid. This episode is a relatively minor setback: failed event bids are common for many cities, and the bidding often has less to do with the global prestige of hosting than with local development goals. In this case, the goals remain in place, but the episode highlights the challenges presented to a Qatari development model based on urban mega-projects and event-based ‘branding’ strategies.

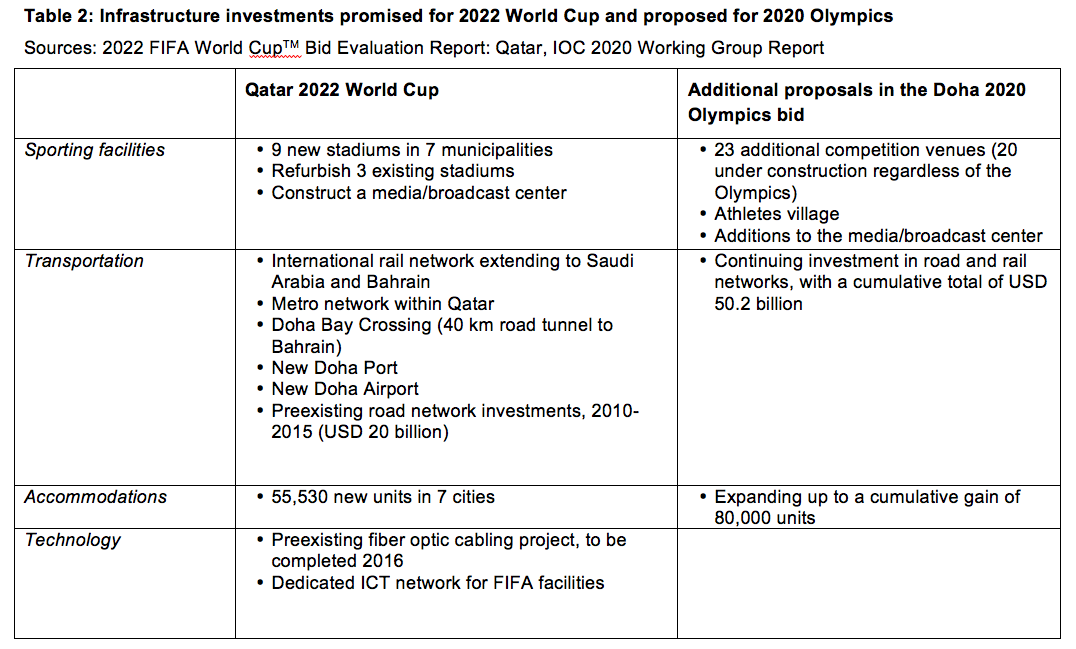

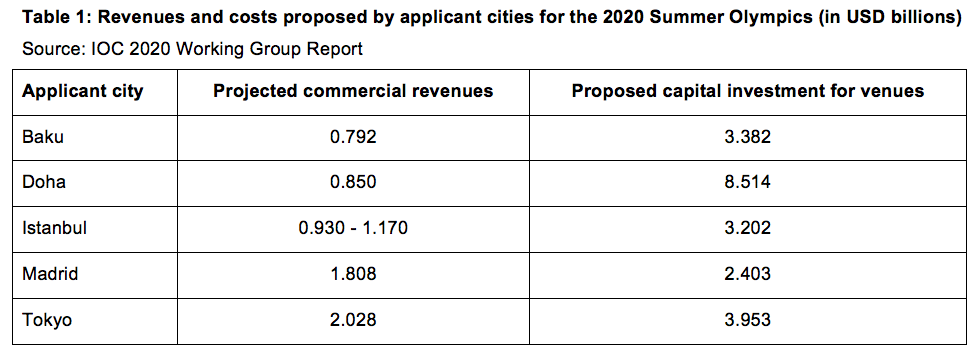

Doha 2020, the Doha bid committee, had presented an ambitious proposal for developing 2020 Summer Olympics infrastructure in tandem with investments already underway for Qatar’s upcoming 2022 FIFA World Cup. The bid committee had proposed infrastructure investment far above levels proposed by the other applicants (Table 1). The magnitude of proposed investment was made possible by including ongoing publically-funded infrastructure investments and a range of public-private real estate ventures related to the World Cup in the bid calculations (Table 2). In addition to ongoing investments in preparation for the World Cup, the bid committee proposed constructing 23 new competition venues around the city and suburbs, and an athletes’ village on the Qatar University campus. Building on the World Cup plans for solar powered stadium-cooling technologies, the Olympic bid proposed a variety of strategies to protect athletes and spectators from high temperatures (rescheduling the games in October instead of the IOC’s preferred August timeline, and scheduling events to avoid midday heat).

At a press conference following the decision, IOC president Jacques Rogge clarified that Doha’s request to delay the games until October (and thus alter traditional broadcasting schedules) did not have an impact on the decision. No further specific comments were provided. Some commentators have interpreted the decision as a rebuke to Qatar and Doha’s overly-ambitious plans. The IOC’s review of the applicants, available in its final working group report, provides more insight. The committee expresses concerns that Doha’s plans are far too ambitious and fail to address deeper structural challenges: the Doha investment budget is substantially higher than any recent host city; the scale of construction is logistically ambitious relative to the timeline; the solar cooling-technologies have not been tested on a large scale; and despite future plans for the city’s ecological sustainability, Doha’s current carbon-dependent infrastructure would significantly increase the environmental footprint of the 2020 Olympics.

Putting this bid in broader context, this episode points to challenges faced by two interwoven ‘political branding’ and development strategies. Through a variety of public and public-private initiatives, the Qatari state has devised a strategy for building a knowledge economy (seen prominently in initiatives like the Qatar Foundation’s ‘Education City’ projects) in an environmentally “sustainable” urban setting (e.g. solar powered building technologies). This strategy is described in the Qatar National Vision, a national plan frequently referenced in event bidding documents, including Doha 2020’s vision statement. Bidding and preparing for megaevents–most prominently the World Cup– is one vehicle for facilitating these investment strategies. Event hosting even seems to be emerging as a national Qatari geopolitical strategy: One analyst has argued that Qatari offers to host diplomatic functions (ranging from the Taliban’s first foreign diplomatic office to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change COP 18 summit, upcoming in November) and international events is tightly coupled with efforts to brand the city-state as a political and business crossroads. In a response to the IOC’s decision, Doha 2020 CEO Noora Al Mannai echoed this tight coupling of event-based investment, urban planning strategy, and plans for national economic restructuring: “The good news is that our National Vision and master plan guarantees an urban fabric that places sport at its heart; therefore Doha will be ready to host the Games whenever the IOC leadership grants the wider IOC membership the opportunity to decide the fate of bidding nations at this stage of the process.”

As with other Gulf cities, Doha’s rapid ascent to "world city" status entails large-scale investment in the built environment and in the city’s "brand value." Urban investment and branding strategies, like the Olympics bid, reflect what one group of urban studies scholars has recently discussed as a practice of "worlding cities." In a 2011 edited volume on the topic, these scholars highlight the increasing prevalence of urban development strategies funded by regional institutions with global ambitions, and inspired by urban design models from other newly-rising global cities (like Dubai or Singapore), rather than the Euro-American models which have conventionally served as templates for large scale urban design. In their pursuit of what these urbanists call “the art of being global”, cities with aspirations to global prominence are becoming sites of intervention for furthering local and national interests by applying urban models drawing on examples from comparable cities to justify planning interventions, and building new investment and expertise communities across newly-rising world cities. In Doha’s case, these attempts to build a national knowledge economy and claim a place for the city on the world stage is explicitly linked to event-led investment: the planning structures mandated by organizations like the IOC mean that event preparations provide a ready-made model for redesigning cities. The 2006 Doha Asian Games, 2011 Pan-Arab Games, 2016 and 2020 Olympic bids, and 2022 World Cup have all been marketed as catalysts for redeveloping the Qatari economy around Doha as a global model for sustainability-oriented urban designs and technologies.

The IOC’s decision was based on a wide range of considerations and alternative options, many of which are outside of the Doha planners’ control. Despite this setback, Doha’s real estate developers, urban planners, and city boosters seem likely to continue an event-led strategy as an important component of Qatar’s urban design and national development plans. Perhaps we can expect a Doha 2024 Olympics bid?